Mosaic House

Mosaic House, Chiswick

Spitalfields, Shoreditch and Penge have established themselves as London’s hottest spots when it comes to street art, where you will find uncensored, clandestine and sometimes sanctioned works adorning any spare wall or surface in reach of stealthy street artists.

Yet, it is in a leafy residential road in Chiswick that you will find one of the capital’s most extraordinary street art projects. Upon close inspection, you will discover this is not an ephemeral painted mural soon to be vanquished by the elements, but a very tangible tiled skin layer wrapped around a terraced Victorian dwelling, which has since been named: Mosaic House.

The house belongs to the anarchic mosaic artist Carrie Reichardt who started her artistic career producing mosaics for community centres across the UK, whilst many galleries censored or outright turned down her works. Famously in 2001 the Tate Modern’s director Nicholas Serota refused to consider displaying mosaics, suggesting the medium was not considered graphic arts but decorative and as such the remit of the V&A.

A new breed of mosaicists are challenging this assumption and in its scope Mosaic House is very much a work of art. Besides its technical achievement like much modern art it is radical, challenging and likely to please some whilst alienating others.

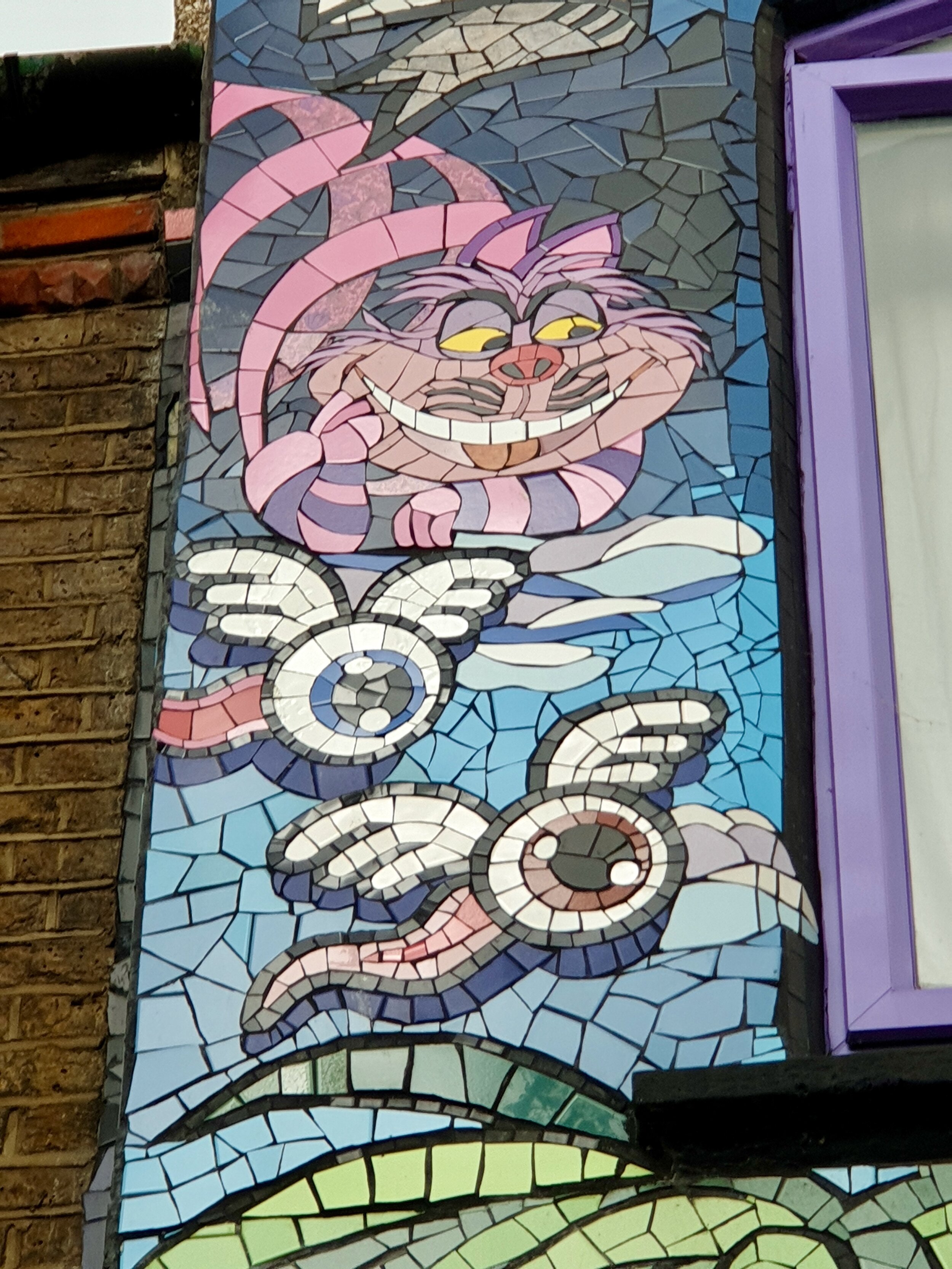

When it comes to appreciating art, I believe first impressions are important. On my first visit to Mosaic House, 80s skateboards style artwork immediately came to mind, but a closer look revealed many themes spanning graffiti art, pop culture past and present, poetry and plenty of social commentary.

Part of this maelstrom of ideas is due to the participation of some of the best mosaic artists around the world who contributed to finishing the house in 2018, in what has been described as a ‘massive push’, almost 20 years since Reichardt embarked on the project.

A keen social campaigner, Reichardt first began working on the rear of the house with the idea of creating a memorial to Luis Ramirez, a death row inmate executed in the state of Texas in 2005. Ramirez who befriended Reichardt was able somehow to post her his prisoner ID, which can be seen in a resin bubble.

Memorialised are also the Angola Three, who were Black Panther activists incarcerated for almost 40 years in Louisiana in 1973, convicted for murder, but finally freed in the 2010s after a controversial miscarriage of justice.

Reichardt’s anti-conformism is not solely expressed in political activism, but also in her own artistic manifesto, which has presumably been moulded by her struggle in being accepted by the establishment.

Good examples of this are the two English Heritage styled blue plaques awarded by the English Hedonists. One of them reads 'The Treatment Rooms, 2002 - Now’ where ‘Lots of people lived here and partied hard’.

Along with other humorous depictions, like the You’ve gotta fight for your right to be arty! speech bubble (surely a Bestie Boys reference), are inspirational quotes from a variety of sources including Martin Luther King and Thomas Paine. Even the King James Bible is quoted with a passage from Proverbs 29:18 ‘Where there is no vision the people perish’.

And like most contemporary artists, Reichardt’s vision also includes a commentary on climate change, with a depiction of the Tower, St Paul’s and other cherished London buildings being swallowed by a massive wave, alluding to the Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai.

As far as I can tell this is one of two visual references to London, the other being the black cab parked to the right of the house, also fully mosaicked. On a metaphorical level Mosaic House can be seen as a graphic representation of the capital’s multiculturalism. Like fusion cuisine blending disparate flavours, it mixes artistic genres with exotic folklore, drawing inspiration from fictional literature, popular music and race identity, drawing ideas from disparate times and places. It’s hard to think about a single work in which 18th century Japanese art could seamlessly sit comfortably alongside, Aztec iconography, Mexican Day of the Dead imagery, Alice in Wonderland illustrations, Ogee & Gothic pointed arches, trailer park doll heads and other oddities being spied upon by winged eyes flying about, an inverted all seeing eye and the infamous triple-eyed fish from the Simpsons series.

As a whole Reichardt has been able to create a remarkably cohesive work. Its overall effect may be cartoonish, yet there’s a clever understanding of colour schemes which manages not to overwhelm but to invite the viewer to discover its wonderful secrets.

There is so much to write about Mosaic House, but the best way to appreciate its breath would be a lengthy visit. It can be enjoyed on many levels: a Where’s Wally game, a celebration of life or a mourning of death, a spiritual shrine or a cynical scathing of religious orthodoxy. More radical thinkers, will be able to share in Reichardt’s subliminal defiance against the powers that be whilst sniggering at her self-deprecation.

Such a visit to suburban Chiswick could be approached as a pilgrimage, just like a thousand years ago when devout Christians travelled to the great Byzantine churches to wonder at their mosaics full of mystical stories and fantastical imagery.

Mosaic House, left window bay